A benchmark for random memory accesses, with the aim to prove that there is no such thing as O(1) memory accesses on modern hardware, but rather that it is O(√N).

list_traversal.c - Program to calculate random write for RAM

list_traversal_RAM_data.txt - Results of random write for RAM

list_traversal_pmem_reattempted.c - Program to calculate random write for RAM

list_traversal_PMEM_data.txt - Results of random write for PMEM

- Clone it - git clone github.com/emilk/ram_bench

- Compile it - clang++ -std=c++11 -stdlib=libc++ -O3 list_traversal.cpp -o list_traversal

- Run it - ./list_traversal

- Generate plots - gnuplot plot.plg

- Look at them pretty images!

If you have studied computing science, then you know how to do complexity analysis. You’ll know that iterating through a linked list is O(N), binary search is O(log(N)) and a hash table lookup is O(1). What if I told you that all of the above is wrong? What if I told you that iterating through a linked list is actually O(N√N) and binary searches as well as hash lookups both are O(√N)?

Don’t believe me? By the end of the blog post you will. I will show you that accessing memory is not a O(1) operation but O(√N). This is a result that holds up both in theory and practice. Let’s start with the latter:

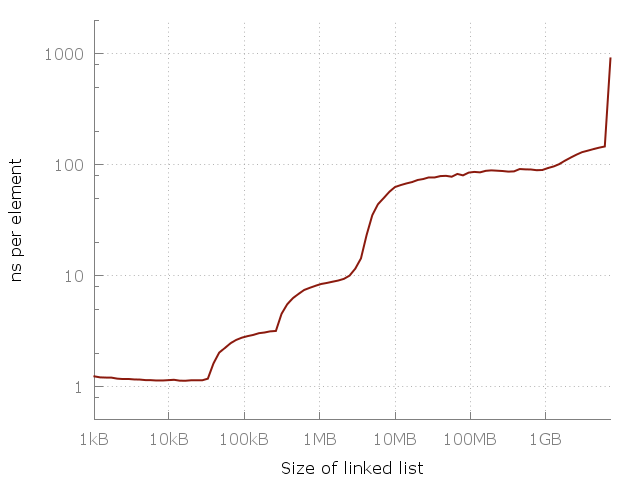

Here’s a simple program that iterates through a linked list of length N, ranging from 64 elements up to about 420 million elements. Each node consists of a 64 bit pointer and 64 bits of dummy data. The nodes of the linked list are jumbled around in memory so that each memory access is random. I measure iterating through the same list a few times, and then plot the time taken per element. This means that we should get a flat plot if random memory access is O(1). This is what we actually get:

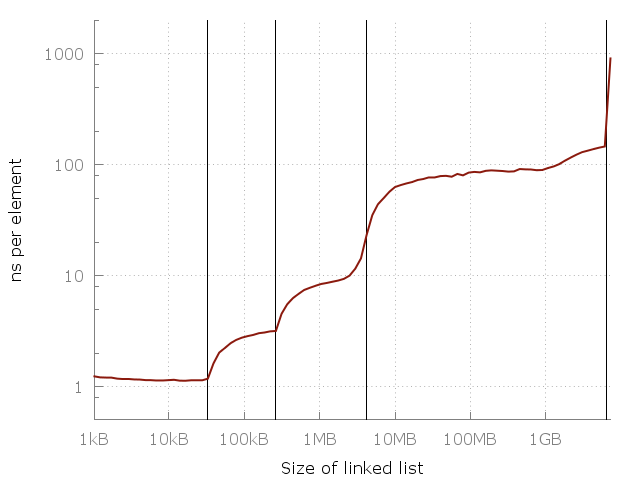

Note that this is a log-log graph, so the differences are actually pretty huge. We go from about one nanosecond per element all they way up to a microsecond! But why? The answer, of course, is caching. The system memory (RAM) is actually pretty slow and far away and so to compensate the clever computer designers have added a hierarchy of faster, closer and more expensive caches to speed things up. My computer has three levels called L1, L2, L3 of 32 kiB, 256 kiB and 4 MiB each. I have 8 GiB of RAM, but when I ran my experiment I only had about 6 GiB free - so in the last runs there was some swapping to disk (an SSD). Here’s the same plot again but with my RAM and cache sizes added as vertical lines:

So that settles it, right? As my memory consumption goes up, I have to rely on slower and slower memory to get the job done, ultimately swapping to disk.

Now you may be thinking that this is all trivial. Surely I (or someone richer than me) could purchase enough fast L1 type memory to fit all the data, and that would yield a flat graph. Sadly, 6 GiB of L1 memory would be way more that could fit on a CPU die, so it would need to be further away, increasing the latency of the data. And if my problem grew even more I would need even more RAM taking up even more space requiring it to be even further from my CPU, making it slower still. But how much slower? Let’s do some thinking.

The limit on the speed for accessing a piece of information is the delay in communication, which depends on the distance between the CPU and that information. The limiting factor in a modern computer is the speed of an electrical signal, but in theory it is the speed of light. Within one clock cycle of a 3GHz CPU, light reaches only about a decimeter. So to roundtrip, any memory that should be instantly accessible can be at most 5cm (2 inches) from the CPU.

So how much information can we fit within a certain distance r from the cpu? Intuition tells us the answer should be proportional to r³ (i.e. a sphere of RAM). In practice computers are actually rather two-dimensional - this is due partly to form-factor, but also due to problems with cooling. A two-dimensional computer gives gives us a memory limit of r² (a disk of RAM). This r² also holds true for even more distant memory, such as data centers (which are spread out on the two-dimensional surface of the earth). So the practical limit of the amount of information within a radius r is I ∝ r².

But can we, in theory, do better? To answer that, we need to learn a bit about black holes and quantum physics!

The amount of information that can fit within a sphere with radius r can be calculated using the Bekenstein bound, which says that the amount of information that can be contained by a sphere is directly proportional to the radius and mass: I ∝ r·m. So how massive can a sphere get? Well, what is the most dense thing in existence? A black hole! It turns out that the mass of a black hole is directly proportional to its radius, m ∝ r. This means that the amount of information that can fit inside a sphere of radius r is I ∝ r². And so we come to the conclusion that the amount of information contained in a sphere is bounded by the area of that sphere - not the volume!

In short: if you try to squeeze too much L1 cache onto your CPU it will eventually collapse into a black hole, and that would make it awkward to get the results of the computation back to the user.

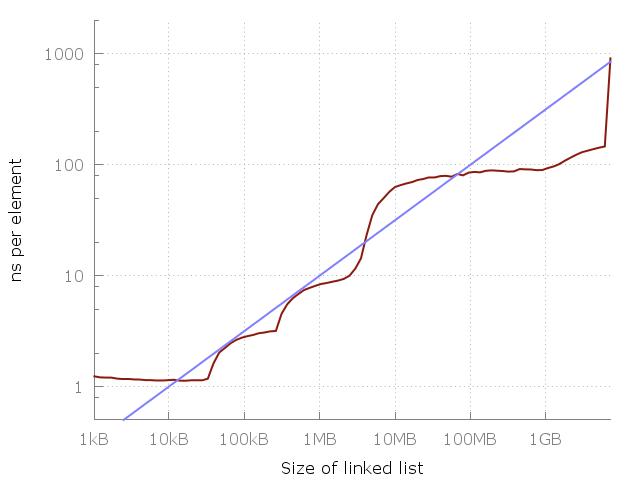

So we come to the conclusion that I ∝ r² is not only the practical limit, but also the theoretical limit! This means the laws of physics sets a limit of the latency of memory: To access any of N bits of data, you will need to communicate a distance that is proportional to O(√N). In other words, for each 100-fold increase in problem size, we expect to see a 10-fold increase in the time it takes to access one element. And that is exactly what our data shows!

Here the blue line corresponds to a O(√N) cost of each memory access. Are you convinced yet?

Now, to be sure, the reason the measured data so closely follows O(√N) is probably not due to the theoretical limits explained above - we are far away from having RAM as information dense as a black hole! The theoretical limit is for now just that - theoretical - but as it happens the practical results follow it very closely, at least in this data. It’s hard to say exactly why - it could be due to the two-dimensional layout of most computers mentioned above, or some complex emergent law involving the cost of producing fast memory. Whatever the reason, the results still stand: for practical and theoretical purposes alike, the cost of a random memory access follows O(√N).

The cost of a memory access depends on the amount of memory you are accessing as O(√N). This means that iterating through a linked list is a O(N√N) operation. A binary search is a O(√N) operation. A hash map lookup is a O(√N) operation. In fact, looking up something randomly in any sort of database is a O(√N) operation.

Note that the above results holds only for random memory accesses. If you access N bits of memory in a predictable fashion (e.g. sequentially) we still get O(N), since the cpu can prefetch the data that is needed ahead of time. A random memory access cannot, per definition, be predicted.