ready_set_boole is a 42 project introducing the basics of boolean algebra.

⚠️ This guide assumes you are already an experienced programmer, and are familiar with classic data structures (i.e. stacks and binary trees).

fn adder(a: u32, b: u32) -> u32;You must write a function that takes as parameters two natural numbers a and b and returns one natural number that equals a + b. However the only operations you’re allowed to use are:

&(bitwise AND)|(bitwise OR)^(bitwise XOR)<<(bitwise left shift)>>(bitwise right shift)=(assignment)==,!=,<,>,<=,>=(comparison)

-

Space:

$O(1)$ -

Time:

$O(1)$

This means that your function should execute roughly the same number of operations, regardless of the size of the numbers.

By size we don't mean the number of bits, but the actual value of the numbers.

If we really simplify this exercise, it basically asks us to add two numbers in base 10, using only operations from base 2.

A base means how important digits in a number are.

In base 10, the rightmost digit is the unit, the next digit is the tens, the next is the hundreds, etc.

This number is equal to:

Given that we use base 10 in our daily lives, we are used to it and don't even think about the previous calculation. But what if we used another base?

In base 2, the rightmost digit is the unit, the next is the twos, the next is the fours, etc.

If we perform the same calculation as before, we get:

Base 2 is also known as binary, and it's the base used by computers.

It may sound weird, but to really nail this exercise, we need to review how to add two numbers in base 10.

Let's take the following example:

For each column:

- We sum the digits

- If needed, carry the excess to the next column (adding a little "1" on the left)

In our example:

In base 2, the same principle applies, but we have fewer digits to work with.

Let's take the following example of

For each column:

- We sum the digits

- If needed, carry the excess to the next column (adding a little "1" on the left)

In our example:

Do you see the pattern?

- The combinations of a

$1$ and a$0$ give a$1$ . - The combination of two

$1$ gives a$0$ and carries a$1$ to the next column.

If you already know about bitwise operations, you might have noticed that the previous examples are respectively the results of:

- a bitwise XOR

- a bitwise AND followed by a left shift

The XOR operation is a bitwise operation that returns

If you XOR the numbers

The AND operation is a bitwise operation that returns

If you AND the numbers

The left shift operation moves the bits to the left by a certain number of positions, adding

For example, if we left shift

Let's take once again the example of summing

If we XOR them, we get:

If we AND them and left shift the result, we get:

Finally, XORing the result with the carry gives us the final result:

If you try to implement this solution, you will notice that it only works for one carry.

Good luck implementing it for multiple carries!

fn multiplier(a: u32, b: u32) -> u32;You must write a function that takes as parameters two natural numbers a and b and returns one natural number that equals a * b. However the only operations you’re allowed to use are:

&(bitwise AND)|(bitwise OR)^(bitwise XOR)<<(bitwise left shift)>>(bitwise right shift)=(assignment)==,!=,<,>,<=,>=(comparison)

-

Space:

$O(1)$ -

Time:

$O(1)$

If you are not familiar with bitwise operations, you might be tempted to use a loop to add a to a result b times.

pub fn multiplier(a: u32, b: u32) -> u32 {

let mut result = 0;

for _ in 0..b {

result = adder(result, a);

}

return result;

}This works. Everything goes well.

However, it has a complexity of

i.e. it takes

$n$ iterations to complete.We are working with

u32, so the worst case scenario is$2^{32}$ iterations =$4 294 967 296$ .

There is a much faster way to multiply two numbers using bitwise operations.

Up to 4 million times faster, to be exact.

Let's take the example of multiplying

If we look at it, we don't really see any pattern like in the previous exercise.

However, putting the base 10 multiplication "on paper" as we did before, we can see that it's just a series of additions.

Rather, we can note it as

To be clearer, let's rewrite the operation as:

To sum things up, we multiply the multiplicand by each digit of the multiplier, shifting appropriately the result to the left.

e.g.

$6 * 5$ , shifted by$1$ , so$6* 50$

Now, we need to do the same thing, in base 2.

Unlike base 10, we only have two digits:

- If the digit is

$0$ , we add$0 * \text{multiplicand}$ to the result → nothing to do. - If the digit is

$1$ , we add$1 * \text{multiplicand}$ to the result.

Let's take the example of multiplying

If we break it down in partial products as we just saw:

In a more readable way:

We added the implicit zeros that were absent in the previous example.

Which is equal in base 10 to:

All good! We can see that the result is indeed equal to

To recap:

- We iterate through the bits of

b.

We can do this by shifting

bto the right byi.

- If the bit is

$1$ , we addato the result, shifted by the positioniof the bit.

💡 To check if the rightmost bit is 0 or 1, we can simply check if

rightmost_bit & 1 == 0

We now have our clean solution!

We are working with

u32, so the worst case scenario is$32^2$ iterations =$1024$ .

$4294967296 / 1024 = 4194304$ , literally 4 million times faster.

fn gray_code(n: u32) -> u32;You must write a function that takes an integer

nand returns its equivalent in Gray code.

This exercise is simpler than the others in the sense that it does not require us to convert decimal problems to Boolean algebra.

The Gray Code is a variant of binary that was invented to facilitate transmissions, by making each consecutive value different from its previous one by only one bit.

It's a bit confusing, but for example,

$4$ in Gray code is written$0110$ , and$5$ is written$0111$ .Here for instance, only the last bit has changed. That is the concept of Gray code.

The purpose of Gray code and its uses are more complex, but what really matters to us here is: how do we translate normal binary to Gray code?

Well, it is actually quite simple now that we are comfortable with Boolean algebra.

As said before, its recipe is just a set of bitwise operations:

- We initialize a number (our to-be Gray number) to 0

- We copy the most significant bit (the one all the way left) to this number

- We then append to the right of this number, the result of XOR on each bit and its neighbor to the right

To make it clearer, let's take the example of

- We initialize our Gray number to

$0$ . - We copy the most significant bit (1 101) to our Gray number, so it becomes

$1$ . - We XOR the first bit with the second bit: 11 01.

-

$1 \oplus 1 = 0$ , so we append$0$ to our Gray number. -

It becomes

$10$ .

-

- We XOR the second bit with the third bit: 1 10 1.

-

$1 \oplus 0 = 1$ , so we append$1$ to our Gray number. -

It becomes

$101$ .

-

- We XOR the third bit with the fourth bit: 11 01.

-

$0 \oplus 1 = 1$ , so we append$1$ to our Gray number. -

It becomes

$1011$ .

-

And that's it! We're done converting

💡 We are working with 32-bit integers, so you can either perform those operations 32 times, or determine the bit length

$x$ and perform those operations$x$ times.We then get a complexity of

$O(x)$ , where$x$ cannot exceed$32$ , and will most likely be much smaller (e.g.$O(4)$ for converting$13$ ).

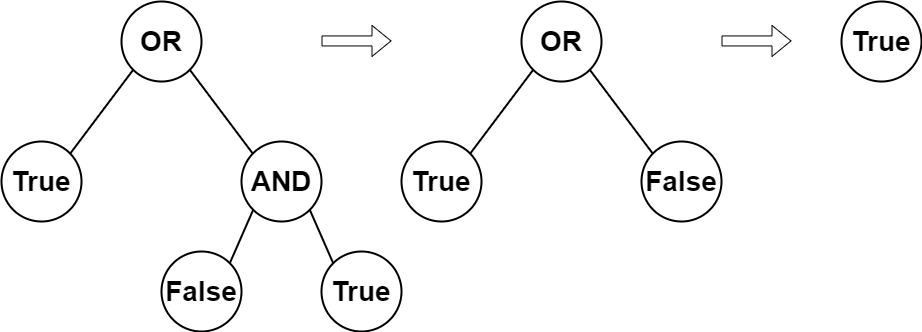

fn eval_formula(formula: &str) -> bool;You must write a function that takes as input a string that contains a propositional formula in reverse polish notation, evaluates this formula, then returns the result.

-

Space:

$O(n)$ -

Time:

$O(n)$

This means that, for an input

Unless you really implement a bad solution, the execution time should be linear in any case here.

This one is actually pretty simple.

Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) is a way to write mathematical expressions without parentheses.

For example, the expression

$(3 + 4) * 5$ can be written in RPN as3 4 + 5 *.

It was already used in the Module 09 of the C++ modules, so you might be familiar with it.

You basically push any operand you encounter to a stack, and when you encounter an operator, you pop the last two operands, apply the operator, and push the result back to the stack.

Here is a simplified version of the algorithm:

for c in chars {

if c == operand {

stack.push(operand);

}

else {

let b = stack.pop();

let a = stack.pop();

match c {

operator => stack.push(a operator b),

some_other_operator => stack.push(a some_other_operator b),

_ => {

println!("Invalid operator");

return false;

}

}

}

}💡 You can use a

Vecas a stack, and use thepopandpushmethods to manipulate it, it's exactly the same.

Now we just need to adapt this algorithm to what the exercise asks:

match c {

'&' => stack.push(a && b),

'|' => stack.push(a || b),

'^' => stack.push(a ^ b),

'>' => stack.push(!a || b),

'=' => stack.push(a == b),

_ => {

println!("Invalid operator");

return false;

}

}Do not forget to handle the

!operator, which is unary.

And that's it! You have your solution.

⚠️ From exercise 05 onwards, we will start to work with more complex concepts, such as Negation Normal Form and Conjunctive Normal Form.For those purposes, it might be good implementing a Binary Tree to represent the formula.

The logic is the same as with the stack, but there is a lot of initial code to write to set up the tree.

fn print_truth_table(formula: &str);You must write a function that takes as input a string that contains a propositional formula in reverse polish notation, and writes its truth table on the standard output.

A formula can have up to 26 distinct variables (A...Z), one per letter. Each variable can be used several times.

-

Time:

$O(2^n)$

This exercise is a bit more complex than the previous one, but it does not really require any new concepts.

We will not cover everything here, but we will give you a hint on how to proceed.

- Determine the variables in the formula.

💡 To the accepted characters from the previous exercise, simply add those between the ASCII

AandZ, and push any of them to a vector (watch out for duplicates).

- Generate all possible sets of values for the variables.

💡 We will cover this later, but basically looking at all possible boolean combinations.

This set of combination has a size of

$2^n$ , where$n$ is the number of variables.

- Evaluate the formula for each set of values.

💡 You can use the previous exercise to evaluate the formula.

Simply replace the variables by their values in the set, and evaluate the formula.

For example, if you have the set

[true, false, true], replaceAby1,Bby0, andCby1, and calleval_formula.

To generate all possible sets of values for the variables, you can use a recursive function.

Here is a simplified version of the algorithm:

fn generate_sets(variables: Vec<char>, set: Vec<bool>, index: usize) {

if index == variables.len() {

// Evaluate the formula with the set

return;

}

set[index] = true;

generate_sets(variables, set, index + 1);

set[index] = false;

generate_sets(variables, set, index + 1);

}fn negation_normal_form(formula: &str) -> String;You must write a function that takes as input a string that contains a propositional formula in reverse polish notation, and returns an equivalent formula in Negation Normal Form (NNF), meaning that every negation operators must be located right after a variable.

The result must only contain variables and the following symbols:

!,&and|(even if the input contains other operations).

⚠️ As said before, we will start to work with a Binary Tree to represent the formula.Every node of the tree will be an operator, and every leaf will be a variable.

Example:

To complete this exercise, we will need to apply some "rewrite rules" to the tree, provided by the subject.

- Elimination of double negation

- Material conditions

- Equivalence

- De Morgan's laws

- Parse the formula to build the binary tree.

- Apply all the mentioned rewrite rules to the tree.

⚠️ XOR is not mentioned in the rewrite rules, you have to figure out how to rewrite it!

- Rebuild the formula from the tree.

To develop step 2 a bit more, here is how you can apply some rewrite rules:

- Material Conditions: Every node

>with childrenAandB, will need to become a node|with children!AandB. - De Morgan's laws: Every node

!with a child&with childrenAandB, will need to become a node|with children!Aand!B.

💡 Use a recursive function to apply the rewrite rules to the tree.

fn conjunctive_normal_form(formula: &str) -> String;You must write a function that takes as input a string that contains a propositional formula in reverse polish notation, and returns an equivalent formula in Conjunctive Normal Form (CNF). This means that in the output, every negation must be located right after a variable and every conjunction must be located at the end of the formula.

This sounds very similar to the previous exercise, but it is actually a bit more complex.

Yes, you first need to convert the formula to NNF, but then you need to apply a few more rules to convert it to CNF.

The last rewrite rule is the Distributivity.

Distibutivity basically allows us to "distribute" a conjunction over a disjunction, and vice versa.

🤓 More simply put, it means that if you have a

|above a&, distributivity allows to "switch" them.That is good news, given that we want to bring all the

&to the end of the formula (i.e. at the upper level of the tree).

- Apply NNF to the formula.

- Build the binary tree.

- Apply the first distributivity rule to the tree.

- Rebuild the formula from the tree.

This being done, you might have an output that looks like this:

Formula: AB&CD&|

CNF: AC|AD|&BC|BD|&&

If we were to convert this CNF back to a tree, it would look like (A | C) & (A | D) & (B | C) & (B | D).

So the objective is achieved, all the & are at the top-level!

However, the RPN notation is not respected, some & are not at the very end of the formula.

The final step is simply to move all the & to the end of the formula (yes, manipulating the RPN string directly).

⚠️ This can be done safely only because all the&are at the top-level. If you were to manipulate an RPN notation without ensuring this, you would most likely break the formula.

fn sat(formula: &str) -> bool;You must write a function that takes as input a string that contains a propositional formula in reverse polish notation and tells whether it is satisfiable.

The function has to determine if there is at least one combination of values for each variable of the given formula that makes the result be ⊤. If such a combination exists, the function returns

true, otherwise, it returnsfalse.

-

Time:

$O(2^n)$

This exercise may sound complex, but you already have all the tools to solve it since exercise 04.

Remember the truth table? It was used to evaluate all possible combinations of values for the variables.

Well, this is the only thing you need to do here.

- Generate all possible sets of values for the variables.

- Evaluate the formula for each set of values.

- If the formula evaluates to

truefor at least one set of values, returntrue. - Return

falseotherwise.

fn powerset(set: Vec<i32>) -> Vec<Vec<i32>>;You must write a function that takes as input a set of integers, and returns its powerset.

-

Space:

$O(2^n)$ -

Time:

$O(2^n)$

The powerset of a set is the set of all its subsets.

That doesn't make it any clearer.

Let's take the set [1, 2, 3].

The powerset of this set is:

[

[], // The empty set

[1], [2], [3], // All the singletons

[1, 2], [1, 3], [2, 3], // All the pairs

[1, 2, 3] // The set itself

]

So, a powerset simply contains all the possible combinations of elements of the set.

To achieve this, we can use the special property of binary numbers.

For a set of size

Moreover, going from 0 and 1 for a set of size

Example: for the set

[1, 2, 3]of length$3$ , we will go from$0$ to$2^3 - 1 = 7$ in binary, and push the values of the set where the bit is1.// 123 0: 000 → [] 1: 001 → [3] 2: 010 → [2] 3: 011 → [2, 3] 4: 100 → [1] 5: 101 → [1, 3] 6: 110 → [1, 2] 7: 111 → [1, 2, 3]

And that's it! We have our powerset.

fn eval_set(formula: &str, sets: Vec<Vec<i32>>) -> Vec<i32>;You must write a function that takes as input a string that contains a propositional formula in reverse polish notation, and a list of sets (each containing numbers), then evaluates this list and returns the resulting set.

Once again, the subject is not very clear, but it is actually quite simple.

This is extracted from the subject, and will help you understand the exercise.

The following logical operations have a counterpart in set theory (they are not the only operations that exist though):

| Boolean Algebra | Boolean Algebra name | Set Theory | Set Theory name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negation (NOT) | Complement | ||

| Disjunction (OR) | Union | ||

| Conjunction (AND) | Intersection |

In programming, the symbols for these operations are respectively

!,|, and&.

Let's take the set [1, 2, 3].

The complement of this set is the set of all the numbers that are not in the set.

If we are working with the universal set of all integers, the complement of [1, 2, 3] is

Any number that is not in the set is in the complement.

So technically, the complement of the set is infinite, but the subject specifies that the globally encompassing set is considered to be the union of all the sets given as parameters.

Let's take the sets [1, 2, 3] and [4, 5, 6].

The union of these two sets is [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

Any number that is in at least one of the sets is in the union.

Let's take the sets [1, 2, 3] and [2, 3, 4].

The intersection of these two sets is [2, 3].

Any number that is in both sets is in the intersection.

Now that we demystified those three operations, we know that our function will work exactly like the boolean evaluation function, but with different behaviors for !, |, and &.

- Convert the formula to CNF.

- Parse the formula to build the binary tree.

- Evaluate the formula for each set of values.

- Apply the corresponding set operation to the sets.

fn map(x: u16, y: u16) -> f64;You must write a function that takes as input two integers

xandy, and returns a floating-point number that represents the value of the curve at the point(x, y).You must write a function (the inverse of a space-filling curve, used to encode spatial data into a line) that takes a pair of coordinates in two dimensions and assigns a unique value in the closed interval

$[0, 1] \in \mathbb{R}$ .Let f be a function and let A be a set such as:

$$ f : (x, y) \in [[0; 2^{16} - 1]]^2 \subset \mathbb{N}^2 \rightarrow [0; 1] \subset \mathbb{R} $$

$$ A \subset [0; 1] \subset \mathbb{R} $$

It is easy to get frightened by the mathematical notation, but the instructions are actually quite simple:

- The function that takes two integers

xandycomprised between$0$ and$2^{16} - 1$ , in the set of natural numbers. - It returns a floating-point number

$A$ , comprised between$0$ and$1$ , in the set of real numbers.

To do this, we can use binary once again.

We know that the two inputs will not exceed

💡 We can use the

u32type to store this number.

-

Shift

xto the left by$16$ bits. -

Perform a bitwise OR between

xandy. -

Divide the result by

$2^{32} - 1$ to get a number between$0$ and$1$ .

And that's it! You have your solution.

fn reverse_map(n: f64) -> (u16, u16);You must write the inverse function

$f^{−1}$ of the function$f$ from the previous exercise (so this time, this is a space-filling curve, used to decode data from a line into a space).Let

$f$ and$A$ be the function and set from the previous exercise, then:

$$f^{-1} : A \rightarrow [[0; 2^{16} - 1]]^2 \subset \mathbb{N}^2$$ The above function must be implemented such that the following expressions are true for values that are in range:

$$(f^{-1} \circ f)(x, y) = (x, y)$$

$$(f \circ f^{-1})(x) = x$$

Let's decrypt the mathematical notation.

-

The function

$f^{-1}$ takes a floating-point number$n$ in the set$A$ , and returns a pair of integers$(x, y)$ comprised between$0$ and$2^{16} - 1$ . -

If you apply

$f$ to a pair of integers$(x, y)$ , and then apply$f^{-1}$ to the result, you should get back$(x, y)$ . -

If you apply

$f^{-1}$ to a floating-point number$n$ , and then apply$f$ to the result, you should get back$n$ .

So basically, you need to reverse the operation you did in the previous exercise.

-

Multiply

nby$2^{32} - 1$ to get a number between$0$ and$2^{32} - 1$ . -

Shift

nto the right by$16$ bits to get the originalx. -

Shift

nto the left by$16$ bits, then again to the right by$16$ bits to get the originaly.

- 💬 How can I perform multiplication, using bitwise operators?

- 💬 Grade School Multiplication Algorithm for Binary Numbers explanation

- 📺 Power Set

- 📺 Generate Power set for a given set (bitwise way)