Hashed and Hierarchical Wheels were used as a base for Kernels and Network stacks, and were described by the freebsd, linux people, researchers and in many other searches.

Many modern Java frameworks have their own implementations of Timing Wheels, for example, Netty, Agrona, Reactor, Kafka, Seastar and many others. Of course, every implementation is adapted for the needs of the particular framework.

The concept on the Timer Wheel is rather simple to understand: in order to keep

track of events on given resolution, an array of linked lists (alternatively -

sets or even arrays, YMMV) is preallocated. When event is scheduled, it's

address is found by dividing deadline time t by resolution and wheel size.

The registration is then assigned with rounds (how many times we should go

around the wheel in order for the time period to be elapsed).

For each scheduled resolution, a bucket is created. There are wheel size

buckets, each one of which is holding Registrations. Timer is going through

each bucket from the first until the next one, and decrements rounds for

each registration. As soon as registration's rounds is reaching 0, the timeout

is triggered. After that it is either rescheduled (with same offset and amount

of rounds as initially) or removed from timer.

Hashed Wheel is often called approximated timer, since it acts on the certain resolution, which allows it's optimisations. All the tasks scheduled for the timer period lower than the resolution or "between" resolution steps will be rounded to the "ceiling" (for example, given resolution 10 milliseconds, all the tasks for 5,6,7 etc milliseconds will first fire after 10, and 15, 16, 17 will first trigger after 20).

If you're a visual person, it might be useful for you to check out these slides, which help to understand the concept underlying the Hashed Wheel Timer better.

The early variant of this implementation was contributed to Project Reactor back in 2014,

and now is extracted and adopted to be used as a standalone library with benchmarks,

debounce, throttle implementations, ScheduledExecutorService impl and

other bells and whistles.

For buckets, ConcurrentHashSet is used (this, however, does not have any

influence on the cancellation performance, it is still O(1) as cancellation is

handled during bucket iteration). Switching to the array didn't bring change

performance / throughput at all (however, reduced the memory footprint). Array

implementation is however harder to get right, as one would have to allow

multiple strategies for growth and shrinking of the underlying array.

Advancement would be to implement a hierarchical wheels, which would be quite simple on top of this library.

Internally, this library is using nanoTime, since it's a system timer (exactly

what the library needs) best used for measuring elapsed time, exactly as JDK

documentation states. One of the places to read about nanoTime is

here.

Timer Wheel allows you to pick between the three wait strategies: BusySpin

(most resource- consuming), although resulting into the best precision. Timer

loop will never release control, and will spin forever waiting for new tasks.

Yielding strategy is some kind of a compromise, which yields control after

checking whether the deadline was reached or no. Sleeping strategy is

injecting a Thread.sleep() until the deadline. Moving from "system" timer

usually means you don't want to use sleep at all. Except maybe for testing.

Library implements ScheduledExecutorService. The decision was made to

implement this interface instead of Timer, since what the library does has

more to do with scheduled executor service than.

For convenience, library also provides

debounce and throttle for Runnable,

Consumer and BiConsumer, which allow you to wrap any runnable or consumer

into their debounced or throttled version. You can find more information about

debouncing and throttling by following the links above.

JDK Timers are great for the majority of cases. Benchmarks show that they're working stably for "reasonable" amounts of events (tens of thousands).

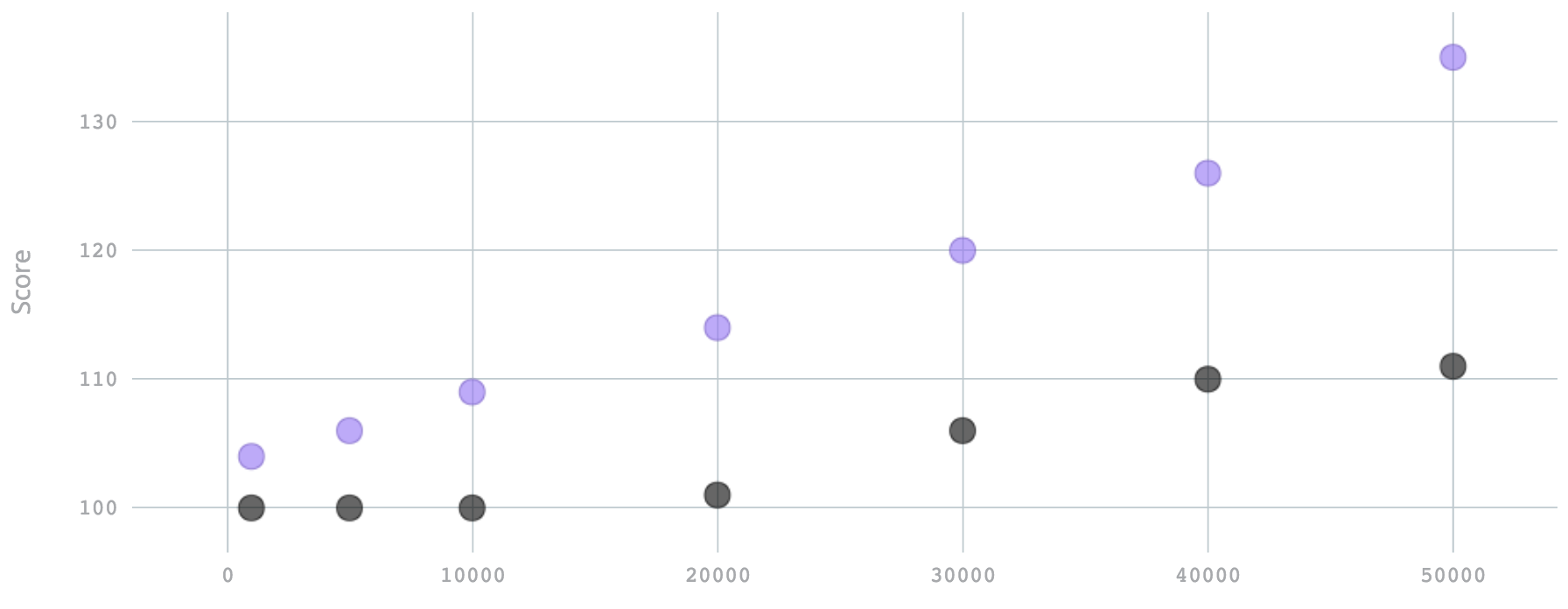

The following charts show the performance of JDK ScheduledExecutorService

(violet) vs HashedWheelTimer (black). The X is the amount of tasks submitted

sequentially, the Y Score axis is the latency until all the tasks were executed.

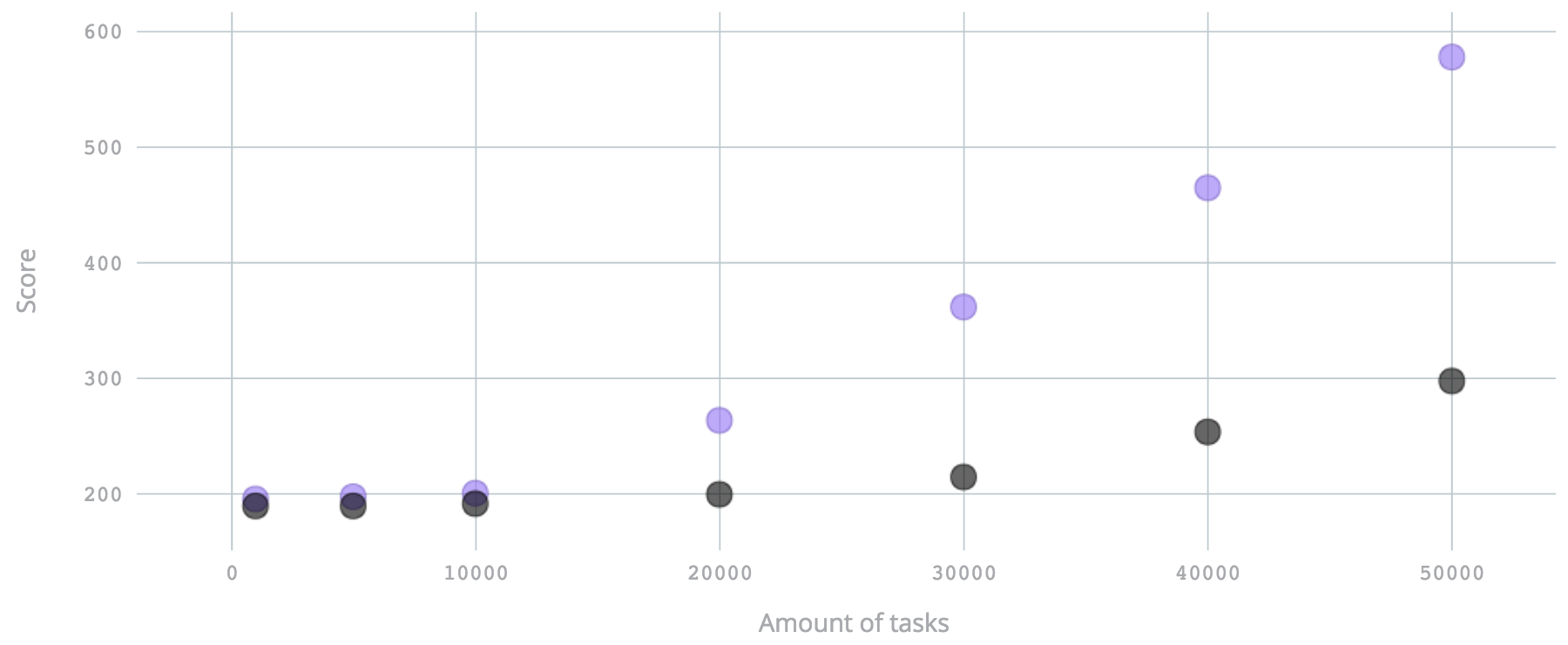

In the following chart, the Y axis is amount of tasks submitted sequentially, although from 10 threads, where each next thread is starting with 10 millisecond delay.

In both cases, 8 threads are used for workers. Changing amount of threads, hash wheel size, adding more events to benchmarks doesn't significantly change the picture.

You can see that HashedWheelTimer generally gives a flatter curve, which means

that given many fired events, it's precision is going to be better.

All benchmarks can be found here. If you think the benchmarks are suboptimal, incomplete, unrealistic or biased, just fire an issue. It's always good to learn something new.

<dependency>

<groupId>com.github.ifesdjeen</groupId>

<artifactId>hashed-wheel-timer-core</artifactId>

<version>1.0.0-RC1</version>

</dependency>Artifact is hosted on Sonatype OSS repository:

<distributionManagement>

<repository>

<id>sonatype-releases</id>

<name>Sonatype Releases</name>

<url>https://oss.sonatype.org/content/repositories/releases</url>

</repository>

<snapshotRepository>

<id>sonatype-snapshots</id>

<name>Sonatype Snapshot</name>

<url>https://oss.sonatype.org/content/repositories/snapshots</url>

</snapshotRepository>

</distributionManagement>Copyright © 2016 Alex P

Distributed under the Eclipse Public License either version 1.0 or (at your option) any later version.