Push_swap is a sorting algorithm implementation designed to efficiently sort numbers using two stacks and a fixed set of instructions (push, swap, rotate). It takes an unordered stack of integers as input and outputs a series of instructions to sort the stack in ascending order, aiming to accomplish this with the least number of moves possible.

- Enhanced Turk Algorithm: This implementation builds upon the Turk Algorithm by Ali Ogun, further improving its efficiency by incorporating additional checks for circular sorting (Full Score!).

- Keeping it fast and simple: Utilizing arrays instead of linked lists for faster execution and a more streamlined coding layout.

- Robust Input Handling: Accepts various forms of input, including a mix of strings and numbers.

- Insightful Diagnostics: The 'diagnostic mode' offers comprehensive insights into the inner workings of the sorting algorithm, providing a detailed description of steps taken to sort a given set of parameters.

The rules of push_swap, detailing the stack setup and allowed moves, are well explained in this article.

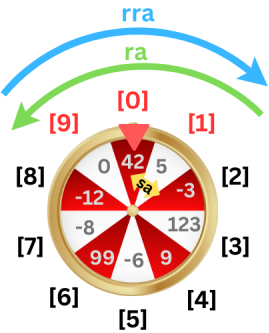

As you can rotate the stacks forward and backwards, I found it helpful to think of them as wheels of fortunes. Let's have a look at stack 'A', which is generated by executing ./push_swap 42 5 -3 123 9 -6 99 -8 -12 0.

- sa: Swap the first and second numbers ([0] and [1]).

- ra: Rotate the stack anticlockwise (or up), each number moves one position up, with the first one becoming the last.

- ra: Rotate the stack clockwise (or down), each number moves one position down, with the last one becoming the first.

- pa: The first number of stack 'A' is moved on top of stack 'B'; all other numbers in 'A' move one position up (not shown).

- pb: The first number of stack 'B' is moved on top of stack 'A'; all numbers in 'A' move one position down (not shown).

While there are several established sorting algorithms available for tackling push_swap, such as radix sort or insertion sort, I found these approaches less intuitive due to the restrictive set of rules that need to be considered. With only two stacks and a limited set of allowed moves, using traditional sorting algorithms often requires additional preprocessing steps like normalizing the numbers or dividing them into chunks. They also don't leverage double rotations or double-reverse rotations, which are essential for achieving solutions with as few operations as possible.

That's why I looked into a solution that is tailored to the specific requirements of push_swap. Ali Ogun describes a simple yet effective approach in this wonderful article, which he coined the 'Turk Algorithm'. Let's look at an example to visualize the key steps:

-

Stack 'A'

2 4 6 7 1 5 3: -

Initialization: Begin by pushing the first two elements from stack 'A' to stack 'B'.

-

Sorting 'B': Move elements from stack 'A' to stack 'B' in such a way that 'B' becomes sorted in descending order.

- This involves finding suitable targets in 'B' for each element in 'A'.

- The target is as close as possible to but smaller than the 'A' element. If no smaller element is found in stack 'B', the largest value in 'B' is selected as the target.

- Move the 'A' element and its corresponding target in 'B' to the top of their respective stacks, choosing the pair that requires the fewest operations to reach the top (the 'cheapest' pair).

- Push the 'A' element onto its target in stack 'B'.

-

Reducing 'A' to 3 Elements: Repeat the sorting process above until only three elements remain in stack 'A'.

-

Sort 'A': Sort the three remaining elements in stack 'A' in ascending order.

-

Restoring 'A': Push elements from stack 'B' back to stack 'A' while ensuring that the resulting stack 'A' is sorted.

- The target in stack 'A' for the top element in stack 'B' is as close as possible but larger. If no larger element is found in stack 'A', the smallest value in 'A' is selected as the target.

- In most cases, the target element in stack 'A' is already positioned at the top. However, the target can also be the bottom element in stack 'A', which is then brought to the top with a single reverse-rotation.

-

Move Smallest Value to Top: Rotate stack 'A' either clockwise or counterclockwise until the smallest value is positioned at the top, resulting in a sorted stack in linear order.

Pushing elements from stack 'A' onto stack 'B' until only three elements remain is done because it's simple enough to sort these remaining values within stack 'A'. If the stack happens to become sorted in ascending order while pushing elements from 'A' to 'B', there is no need to continue the sorting process, and 'A' can be restored right away. The author of the 'Turk Algorithm' considers this in his implementation of push_swap by checking after each 'pb' move if stack 'A' is sorted linearly (with the first element being the minimum and the last one being the maximum).

To fine-tune the algorithm even further, I also took into account whether stack 'A' becomes sorted circularly while pushing, meaning the values are sorted in ascending order, not considering their positions. If so, you can easily bring the minimum value to the top by rotating (forward when the minimum value is in the upper half, backward if it's in the lower half).

Let's examine the (admittedly rather contrived) stack 'A' 8 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0:

-

The original 'Turk Algorithm' requires 21 moves to sort stack 'A' (as of 03/05/24).

-

My enhanced 'Turk Algorithm', which includes checks for circular sorting, only requires 7 moves to sort stack 'A'.

A data structure named 't_stacks' was implemented to hold all necessary information needed for sorting. This way, you can pass the 't_stacks' variable as the sole parameter to functions, making the sorting process and coding layout more streamlined and cohesive.

typedef struct s_stacks

{

size_t size_a; // Number of elements in stack 'A'.

size_t size_b; // Number of elements in stack 'B'.

int *stack_a; // An array containing the elements of stack 'A'.

int *stack_b; // An array containing the elements of stack 'B'.

size_t *target_a; // An array storing the target indices in 'B' for each element in 'A'.

size_t target_b; // The target index in stack 'A' for the first element in stack 'B'.

int *cost; // An array representing the cost associated with moving respective

// element in stack 'A' and its target in stack 'B' to the top.

int *rr; // A flag array showing if double rotation(s) is the cheapest way to move

// respective element in stack 'A' and its target in stack 'B' to the top.

int *rrr; // A flag array showing if double reverse-rotation(s) is the cheapest way to move

// respective element in stack 'A' and its target in stack 'B' to the top.

} t_stacks;Both arrays and linked lists can be used to store integer values. In an array, each value is stored in an element, while in a linked list, each value is stored in a node.

- Memory Efficiency: Arrays typically use contiguous memory allocation, which can be more memory-efficient than linked lists because they don't require extra memory for pointers.

- Cache Locality: Accessing elements in an array can be faster due to better cache locality. CPUs often utilize caching mechanisms that work more efficiently with contiguous memory accesses.

- Random Access: Arrays allow for constant-time random access to elements using indices, which can be advantageous for certain operations.

- Fixed Size: Arrays have a fixed size, which means you need to know the maximum size of your data in advance. This limitation can be a drawback if your data size is dynamic or unknown.

- Dynamic Size: Linked lists can dynamically grow and shrink in size, making them more flexible for handling variable-sized data.

- Dynamic Memory Allocation: Linked lists allocate memory dynamically as nodes are added, allowing efficient memory usage, especially for large datasets.

- Insertions and Deletions: Insertions and deletions at arbitrary positions in a linked list are generally faster than in an array because they involve only pointer manipulation.

- Memory Overhead: Linked lists have additional memory overhead due to the pointers linking nodes, which can be a disadvantage if memory usage is a concern.

-

The maximum size of the stacks is known: It's the number of passed integer values. Therefore, there is no need to dynamically allocate or deallocate memory every time a stack grows or shrinks. Instead, you can initialize with fixed-size arrays and keep track of the stack sizes via members in the data structure ('size_a' and 'size_b').

-

Managing arrays is more straightforward compared to linked lists/nodes, as you can access elements directly using indices.

-

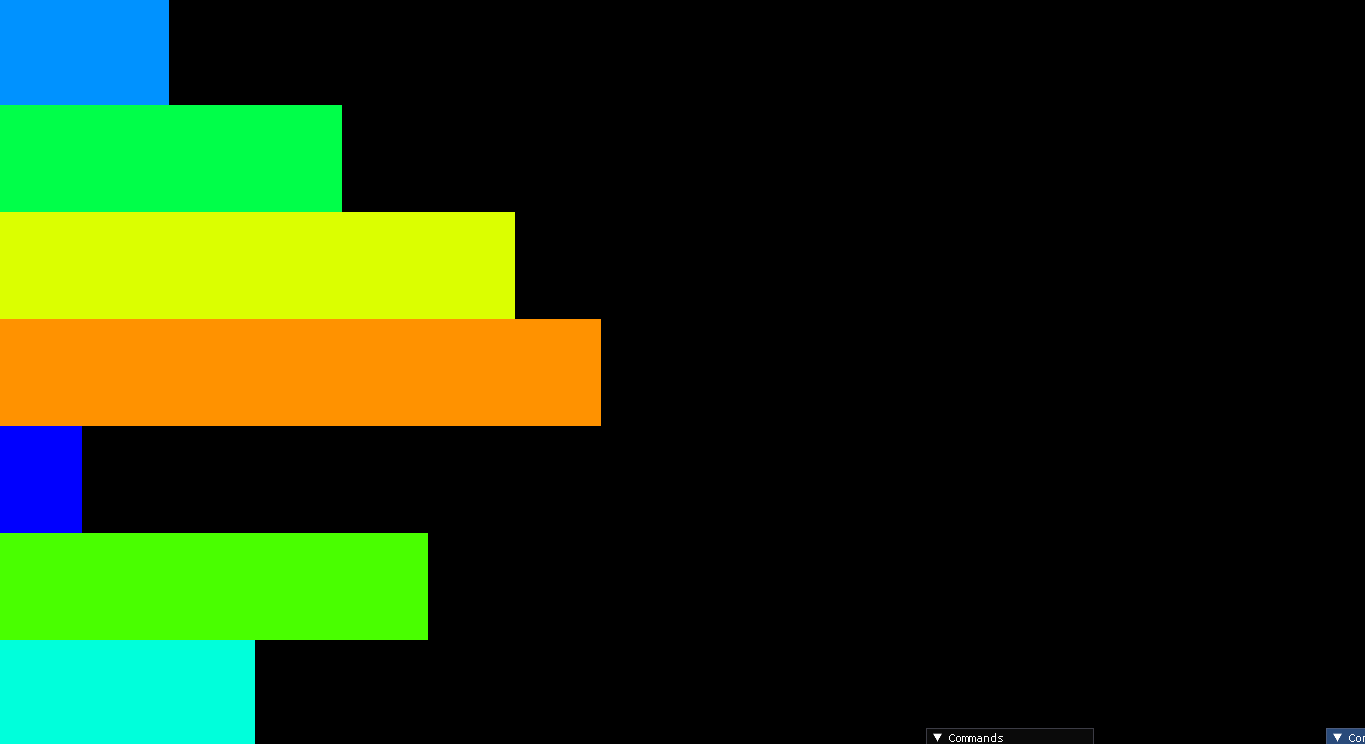

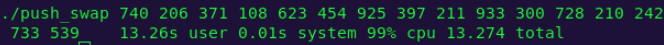

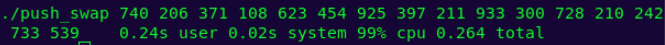

Arrays offer better cache locality, resulting in faster access times for elements, which drastically increases the performance for larger data inputs (tested via

time ./push_swap [LIST OF 1000 RANDOM INT VALUES]:- Sorting 1,000 values using linked lists (as implemented here): 13.27s

- Sorting 1,000 values using arrays: 0.26s (50 times faster!)

- Sorting 1,000 values using linked lists (as implemented here): 13.27s

This push_swap implementation is designed to accept inputs in various forms, for example:

- Integers with one optional sign and leading zeroes (+0 and -0 is accepted):

./push_swap 42 -2 +0 007 +00099 - Integers in a string:

./push_swap "42 -2 0 7 99" - A mix of integers and integer strings:

./push_swap "42 -2" 0 7 "99 88"

The last feature is achieved by first concatenating every parameter with a space delimiter into a single string (using ft_strjoin) and then splitting this string up using space as the delimiter, resulting in a char array of integer values (using ft_split).

Throughout the project, I used printouts to check for issues and to understand how the sorting functions handle any given stack 'A'. The 'diagnostic mode' provides additional information via printouts, such as the status of the data structure and cost calculations, which might help in understanding the algorithm better.

Below, find an excerpt of such a diagnostic printout (slightly edited and commented):

$> ./push_swap 42 -2 0 7 99 88

## Structure Status ## (all values as initialized)

Stack A: 42 -2 0 7 99 88

Stack B:

Target for A: 0 0 0 0 0 0

Cost for A: 0 0 0 0 0 0

RR A: 0 0 0 0 0 0

RRR A: 0 0 0 0 0 0

Target for B[0]: -1

# [...]

-- Calculating Costs to move 'A' elements and their targets to top --

Only using R moves:

A[0] to top (RA): 0 + B[0] to top (RB): 0 = 0 moves needed

A[1] to top (RA): 1 + B[0] to top (RB): 0 = 1 moves needed

A[2] to top (RRA): 2 + B[1] to top (RRB): 1 = 3 moves needed

A[3] to top (RRA): 1 + B[1] to top (RRB): 1 = 2 moves needed

Using RR moves:

A[0]: B[0] to top (RR): 0 + A[0] to top (RA): 0 = 0 moves needed

A[1]: B[0] to top (RR): 0 + A[1] to top (RA): 1 = 1 moves needed

A[2]: B[1] to top (RR): 1 + A[2] to top (RA): 1 = 2 moves needed

A[2]: It is cheaper to move this element and its target with RR than with R!

A[3]: B[1] to top (RR): 1 + A[3] to top (RA): 2 = 3 moves needed

Using RRR moves:

A[0]: B[0] to top (RRR): 2 + A[0] to top (RRA): 2 = 4 moves needed

A[1]: B[0] to top (RRR): 2 + A[1] to top (RRA): 1 = 3 moves needed

A[2]: B[1] to top (RRR): 1 + A[2] to top (RRA): 1 = 2 moves needed

A[3]: B[1] to top (RRR): 1 + A[3] to top (RRA): 0 = 1 moves needed

A[3]: It is cheaper to move this element and its target with RRR than with R or RR!

# [...]

-- Setting target for B[0] element --

Finding Target for B[0]: 42

A[0]: 42 < -2; target: A[-1] # The min. value is chosen as the target if no larger one is found.

A[1]: 42 < 0; target: A[-1]

A[2]: 42 < 7; target: A[-1]

A[3]: 42 < 88; target: A[3]

A[4]: 42 < 99; target: A[3]

Target for B[0]: 42 is A[3]: 88

## Structure Status ##

Stack A: -2 0 7 88 99

Stack B: 42

Target for A: 0 0 1 1 0

Cost for A: 0 1 2 1 0

RR A: 0 0 1 0 0

RRR A: 0 0 0 1 0

Target for B[0]: 3

-- Moving B[0] target to top --

-> A[3]: 88

rra

rra

## Structure Status ##

Stack A: 88 99 -2 0 7

Stack A: -2 0 7 88 99

Stack B: 42

-- Pushing 'B' to 'A' --

pa

## Structure Status ##

Stack A: 42 88 99 -2 0 7

Stack B:

-- Rotating min. value in 'A' to top --

rra

rra

rra

## Structure Status ##

Stack A: -2 0 7 42 88 99

Stack B: - Special thanks to Ali Ogun, whose 'Turk Algorithm' served as the starting point for my sorting logic. You can find his repository here.

- Ali also provides the project badges, which are retrieved from this repository.

- Visualizations were created using the push_swap_visualizer by Emmanuel Ruaud.