The Ports & Adapters Architecture (aka Hexagonal Architecture ) was thought of by Alistair Cockburn and written down on his blog in 2005. This is how he defines its goal in one sentence:

Allow an application to equally be driven by users, programs, automated test or batch scripts, and to be developed and tested in isolation from its eventual run-time devices and databases.

Alistair Cockburn 2005, Ports and Adapters

I've seen some articles talking about the Ports & Adapters Architecture that said a lot about layers. However, I haven't read anything about layers in the original Alistair Cockburn post.

The idea is to think about our application as the central artefact of a system, where all input and output reaches/leaves the application through a port that isolates the application from external tools, technologies and delivery mechanisms. The application should have no knowledge of who/what is sending input or receiving its output. This is intended to provide some protection against the evolution of technology and business requirements, which can make products obsolete shortly after they are developed, because of technology/vendor lock-down.

In this post, I'm going to dive into the following subjects:

The problems of the traditional approach

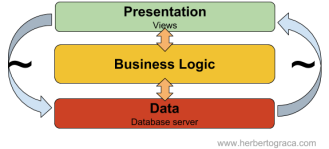

The traditional approach will likely bring us problems both on the front-end side and on the backend side.

On the front-end side we end up having leakage of business logic into the UI (ie. when we put use case logic in a controller or view, making it unreusable in other UI screens) or even leakage of the UI into the business logic (ie. when we create methods in our entities because of some logic we need in a template).

On the back-end side, we can have leakage of the external libraries and technologies into the business logic because we might end up referencing them directly by type hinting, subclassing, or even instantiating the libraries classes inside our business logic.

By 2005, thanks to EBI and DDD, we knew already that what is really relevant in the system are the inner layers . Those layers are the ones where all the business logic lives (or should live), they are the real differential to our competitors. That is the real "application".

But at some point, Alistair Cockburn realised that the top and bottom layers, on the other hand, were simply entry/exit points to/from the application . Although they are actually different, they have nevertheless very similar objectives and there is symmetry in the design. Moreover, if we want to isolate our application inner layers, we can do it using those entry/exit points, in a similar fashion.

To escape the typical layering diagram, we will represent this two sides of the system as left and right, instead of top and bottom.

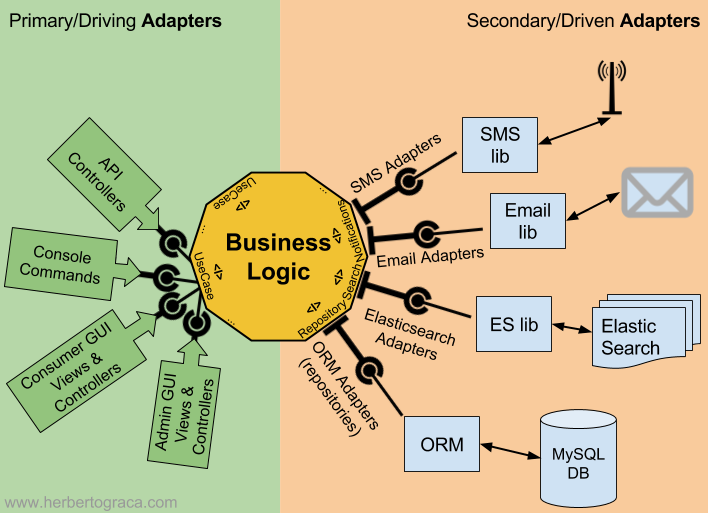

Although we can identify two symmetrical sides of the application, each side can have several entry/exit points . For example, an API and an UI are two different entry/exit points on our left side of the application, while an ORM and a search engine are two different entry/exit points on the right side of our application. To represent that our application has several entry/exit points, we will draw our application diagram with several sides. The diagram could have been any polygon with several sides, but the choice turned out to be a hexagon. Hence the name "Hexagonal Architecture".

The Ports & Adapters Architecture solves the problems identified earlier by using an abstraction layer, implemented as a port and an adapter.

A port is a consumer agnostic entry and exit point to/from the application. In many languages, it will be an interface. For example, it can be an interface used to perform searches in a search engine. In our application, we will use this interface as an entry and/or exit point with no knowledge of the concrete implementation that will actually be injected where the interface is defined as a type hint.

An adapter is a class that transforms (adapts) an interface into another.

For example, an adapter implements an interface A and gets injected an interface B. When the adapter is instantiated it gets injected in its constructor an object that implements interface B. This adapter is then injected wherever interface A is needed and receives method requests that it transforms and proxies to the inner object that implements interface B.

If I managed to confuse you, no worries, I give a more concrete example further below. 🙂

The adapters on the left side, representing the UI, are called the Primary or Driving Adapters because they are the ones to start some action on the application, while the adapters on the right side, representing the connections to the backend tools, are called the Secondary or Driven Adapters because they always react to an action of a primary adapter.

There is also a difference on how the ports/adapters are used:

- On the left side, the adapter depends on the port and gets injected a concrete implementation of the port, which contains the use case. On this side, both the port and its concrete implementation (the use case) belong inside the application ;

- On the right side, the adapter is the concrete implementation of the port and is injected in our business logic although our business logic only knows about the interface. On this side, the port belongs inside the application, but its concrete implementation belongs outside and it wraps around some external tool.

Using this port/adapter design, with our application in the centre of the system, allows us to keep the application isolated from the implementation details like ephemeral technologies, tools and delivery mechanisms, making it easier and faster to test and to create a reusable proof of concept.

We have an application that uses SOLR as a search engine and we use an open source library to connect to it and perform searches.

Using a traditional approach, we will use that library classes directly in our code base, as type hints, instances and/or superclasses of our implementations.

Using ports and adapters we will create an interface, let's call it UserSearchInterface, which we will use in our code when needed as a type hint. We will also create the adapter for SOLR, which will implement that interface, let's name it UserSearchSolrAdapter. This implementation is a wrapper for the SOLR library, so it gets the library injected and uses it to implement the methods specified in the interface.

At some point, we want to switch from SOLR to Elasticsearch. Moreover, for the same search, sometimes we want to use SOLR and other times we want to use Elasticsearch, with that decision being made at runtime.

If we used the traditional approach, we will have to search and replace the usage of the SOLR library for the Elasticsearch library. However, that is not a simple search and replace: the libraries have different ways of being used, different methods with different inputs and outputs, so replacing the libraries will not be a trivial task. And using one library instead of another one, at runtime, won't even be possible.

However, if we used Ports & Adapters, we just need to create a new adapter, let's name it UserSearchElasticsearchAdapter, and inject it instead of the SOLR adapter, maybe just by changing a config in the DIC. To inject a different implementation at run time, we can use a Factory to decide which adapter to inject.

In a similar fashion to the previous example, let's say we have an application that needs a web GUI, a CLI and a web API. We also have some functionality that we want to make available in all three UIs, let's call that functionality UserProfileUpdate.

Using Ports & Adapters, we would implement this functionality in an application service method and think of it as a use case. This service would implement an interface specifying the methods, inputs and outputs.

Each UI version would then have a controller (or console command) that would use that interface to trigger the logic desired and would be injected with the concrete implementation of the service. Here, the Adapter is actually the controller (or CLI Command).

We could then completely change the UI knowing that we would not affect the business logic.

In both the previous examples, testing becomes easier with Ports and Adapters Architecture. In the first examples, we can mock or stub the interface (Port) and test our application without using SOLR nor Elasticsearch.

In the second example, we can test all the UIs in isolation from our application, and our use cases in isolation from the UI by simply giving our service some input and asserting the results.

The way I see it, Ports & Adapters Architecture has only one goal: isolate the business logic from the delivery mechanisms and tools used by the system . And it does so by using a common programming language construct: interfaces.

On the UI side (the driving adapters), we create adapters that use our application interfaces, ie. controllers.

On the infrastructure side (the driven adapters), we create adapters that implement our application interfaces, ie. repositories.

That's all there really is to it!

It is, though, curious to note that this same idea was already published 13 years before, although not explicitly emphasising the objective of isolating the tools and delivery mechanisms from the core of the application.

Any interaction of the system with an actor goes through a Boundary object. As Jacobson describes, an actor can be a human user like a customer or an administrator (operator), but it might also be a non-human "user" like an alarm or a printer, which corresponds to the Driving Adapters and Driven Adapters of Ports & Adapters Architecture.

1992 -- Ivar Jacobson -- Object-Oriented Software Engineering: A use case driven approach

200? -- Alistair Cockburn -- Hexagonal Architecture

2005 -- Alistair Cockburn -- Ports and Adapters

2012 -- Benjamin Eberlei -- OOP Business Applications: Entity, Boundary, Interactor

2014 -- Fideloper -- Hexagonal Architecture

2014 -- Philip Brown -- What is Hexagonal Architecture?

2014 -- Jan Stenberg -- Exploring the Hexagonal Architecture

2017 -- Grzegorz Ziemoński -- Hexagonal Architecture Is Powerful

2017 -- Shamik Mitra -- Hello, Hexagonal Architecture