Layering is a common practice to separate and organise code units by their role/responsibilities in the system.

In an object-oriented program, UI, database, and other support code often gets written directly into the business objects. Additional business logic is embedded in the behaviour of UI widgets and database scripts. This happens because it is the easiest way to make things work, in the short run.

When the domain-related code is diffused through such a large amount of other code, it becomes extremely difficult to see and to reason about. Superficial changes to the UI can actually change business logic. To change a business rule may require meticulous tracing of UI code, database code, or other program elements. Implementing coherent, model-driven objects becomes impractical. Automated testing is awkward. With all the technologies and logic involved in each activity, a program must be kept very simple or it becomes impossible to understand.

Eric Evans 2014, Domain-Driven Design Reference

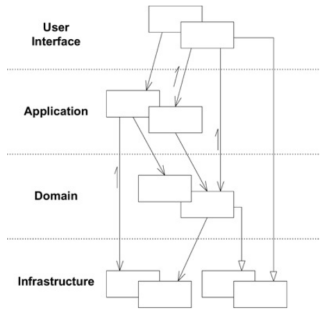

In a layered system, each layer:

- Depends on the layers beneath it;

- Is independent of the layers on top of it, having no knowledge of the layers using it.

In a layered architecture, the layers can be used in a strict way, where a layer only knows the layer directly beneath it, or in a more flexible approach where a layer can access any layer beneath it. Both Martin Fowler and my own experience tells me that the second case seems to work better in practice as it avoids the creation of proxy methods (or even complete proxy classes) in the intermediary layers, and can degrade into the anti-pattern of the Lasagna Architecture (more about it below).

Sometimes the layers are arranged so that the domain layer completely hides the data source from the presentation. More often, however, the presentation accesses the data store directly. While this is less pure, it tends to work better in practice.

Fowler 2002, Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture

The advantages are:

- We only need to understand the layers beneath the one we are working on;

- Each layer is replaceable by an equivalent implementation, with no impact on the other layers;

- Layers are optimal candidates for standardisation;

- A layer can be used by several different higher-level layers.

The disadvantages are:

- Layers can not encapsulate everything (a field that is added to the UI, most likely also needs to be added to the DB);

- Extra layers can harm performance, especially if in different tiers.

Although software development started during the 50s, it was during the 60s and 70s that it was effectively born as we know it today, as the activity of building applications that can be delivered, deployed and used by others that are not the developers themselves.

At this point, however, applications were very different than today. There was no GUI (which only came into existence in the early 90s, maybe late 80s), all applications were usable only through a CLI, displayed in a dumb terminal who would just transmit whatever the user typed to the application which was, most likely, being used from the same computer.

Applications were quite simple so weren't built with layering in mind and they were deployed and used on one computer making it effectively a one-tier application, although at some point the dumb client might even have been remote. While these applications were very simple, they were not scalable, for example, if we needed to update the software to a new version, we would have to do it on every computer that would have the application installed.

During the 1980s, enterprise applications come to life and we start having several users in a company using desktop computers who access the application through the network.

At this time, there were mostly three layers:

- User Interface (Presentation) : The user interface, be it a web

page, a CLI or a native desktop application;

- ie: A native Windows application as the client (rich client), which the common user would use on his desktop computer, that would communicate with the server in order to actually make things happen. The client would be in charge of the application flow and user input validation;

- Business logic (Domain) : The logic that is the reason why the

application exists;

- ie: An application server, which would contain the business logic and would receive requests from the native client, act on them and persist the data to the data storage;

- Data source : The data persistence mechanism (DB), or

communication with other applications.

- ie: A database server, which would be used by the application server for the persistence of data.

With this shift in usability context, layering started to be a practise, although it only started to be a common widespread practice during the 1990s (Fowler 2002) with the rise of client/server systems. This was effectively a two-tier application, where the client would be a rich client application used as the application interface, and the server would have the business logic and the data source.

This architecture pattern solves the scalability problem, as several users could use the application independently, we would just need another desktop computer, install the client application in it and that was it. However, if we would have a few hundred, or even just a few tenth of clients, and we would want to update the application it would be a highly complex operation as we would have to update the clients one by one.

Roughly between 1995 and 2005, with the generalised shift to a cloud context, the increase in application users, application complexity and infrastructure complexity we end up seeing an evolution of the layering scheme, where a typical implementation of this layering could be:

- A native browser application, rendering and running the user interface, sending requests to the server application;

- An application server, containing the presentation layer, the application layer, the domain layer, and the persistence layer;

- A database server, which would be used by the application server for the persistence of data.

This is a three-tier architecture pattern, also known as n-tier. It is a scalable solution and solves the problem of updating the clients as the user interface lives and is compiled on the server, although it is rendered and ran on the client browser.

In 2003, Eric Evans published his emblematic book Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software. Among the many key concepts published in that book, there was also a vision for the layering of a software system:

-

Responsible for drawing the screens the users use to interact with the application and translating the user's inputs into application commands. It is important to note that the "users" can be human but can also be other applications, which corresponds entirely to the Boundary objects in the EBI Architecture by Ivar Jacobson (more on this in a later post);

-

Orchestrates Domain objects to perform tasks required by the users. It does not contain business logic. This relates to the Interactors in the EBIArchitecture by Ivar Jacobson, except that Jacobson's interactors were any object that was not related to the UI nor an Entity;

-

This is the layer that contains all business logic, the Entities, Events and any other object type that contains Business Logic. It obviously relates to the Entity object type of EBI. This is the heart of the system;

-

The technical capabilities that support the layers above, ie. persistence or messaging.

Lasagna Architecture is the name commonly used to refer to the anti-pattern for Layered Architecture . It happens when:

- We decide to use a strict layering approach, where a layer only knows about the layer immediately below it. In such case, we will end up creating proxy methods, and even proxy classes, just so we go through the intermediate layers instead of directly using the layer we need;

- We lead the project into over-abstraction in an urge to create the perfect system;

- Small updates reverberate through all areas of an application, for example, tidying up a single layer can be a large undertaking with huge risks and small payoff.

- We end up with too many layers, which increases the complexity of the overall system;

- We end up with too many tiers, which both increases the complexity and damages the performance of the overall system;

- We explicitly organise our monolith according to its layers (ie. UI, Domain, DB), instead of organising it by its sub-domains/components (ie. Product, Payment, Checkout), destroying modularity and encapsulation of the domain concepts.

Layered Architecture is one more way to provide for separation of concerns, encapsulation and decoupling, by grouping code units by their functional role within the application.

However, as most things in life, too much is counter productive! So the rule-of-thumb is: Use just the layers we need, the tiers we need, and nothing more! We must not get carried away chasing an architectural holy grail, which does not exist. What does exist is a need, and the best possible fit for that need. Which is part of Lean, btw.

Furthermore, it's important to note that this top/down approach to layering is outdated. It is no longer what we should do in modern software development, there are new and better ways of thinking of an application layer. I will talk about then in following posts.

2002 -- Martin Fowler -- Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture

2003 -- Eric Evans -- Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software

2011 -- Chris Ostrowski -- Understanding Oracle SOA -- Part 1 -- Architecture