This package provides an R-native interface to the Valhalla routing engine’s APIs for turn-by-turn routing, isochrones, and origin-destination analyses. It also includes several user-friendly functions for plotting outputs, and strives to follow “tidy” design principles. Please note that this package requires access to a running Valhalla instance.

This package provides an R-native interface to the Valhalla routing engine, and assumes that you have access to a running Valhalla instance. If you don’t, you won’t be able to use any of the functions described in this vignette! Installing and configuring Valhalla is far out of scope for this vignette, but Valhalla is open-source and there are several free resources that you might find helpful.

Here are some example resources to help you get Valhalla up and running:

- Valhalla’s GitHub page has all of the source code and discussions and issue trackers: https://github.com/valhalla/

- Valhalla’s API documentation has a lot of detailed information: https://valhalla.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- GIS-OPS has a helpful guide for installing and running Valhalla: https://gis-ops.com/valhalla-part-1-how-to-install-on-ubuntu/

The rest of this vignette assumes a running Valhalla instance on localhost at the default port 8002.

The function valhallr::route() uses Valhalla to generate detailed

turn-by-turn routing from an origin to a destination. It’s

straightforward to use: you provide origin and destination coordinates

in tibbles with lat and lon columns, along with any number of

optional options, and the API returns an object containing the resulting

trip.

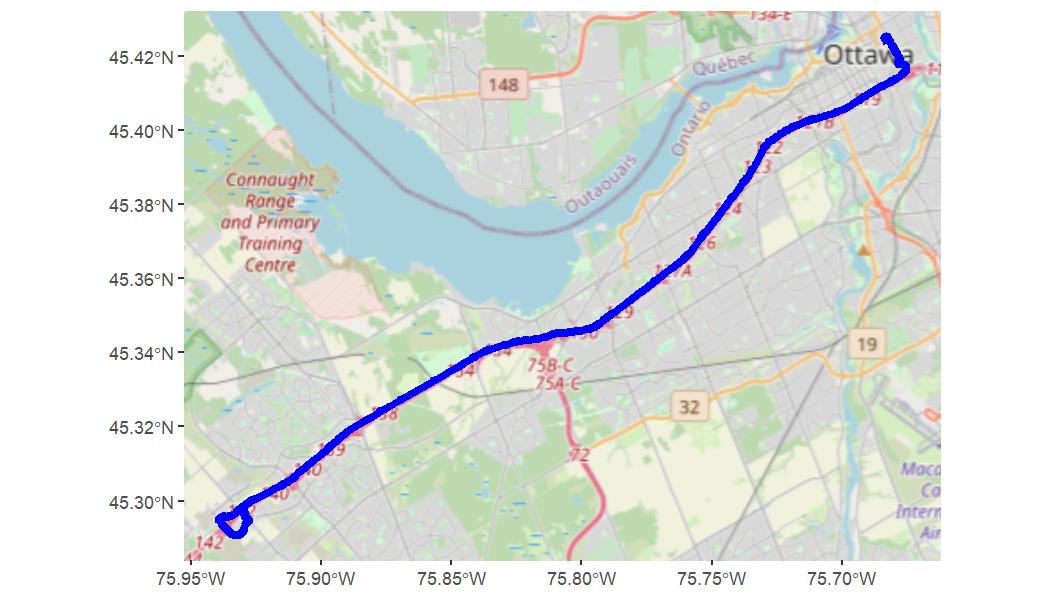

This example shows how to generate driving directions between the

University of Ottawa and the Canadian Tire Centre, a stadium in Ottawa.

It gets these coordinates from the function valhallr::test_data(),

which can return coordinates for several points of interest around

Ontario. It then calls valhallr::route() between these two locations

with all default options, and then passes the result to

valhallr::print_trip().

library(valhallr)

from <- test_data("uottawa")

to <- test_data("cdntirecentre")

t <- route(from, to)

print_trip(t)

#> From lat/lng: 45.4234, -75.6832

#> To lat/lng: 45.2975, -75.9279

#> Time: 19.9 minutes

#> Dist: 28.693 kmWe can see that Valhalla has generated a trip from uOttawa to the Canadian Tire Centre that’s 28.693km long and would take 19.9 minutes to drive. But what does the trip look like?

We can answer this question with the function valhallr::map_trip()

that takes the Valhalla trip object, decodes an embedded shapefile, and

plots the result on a map. (You can use valhallr::decode() to extract

the shapefile yourself for other purposes.) The map_trip() function

supports an interactive map using leaflet or an static map using

ggplot2. Here we’ll generate a static map.

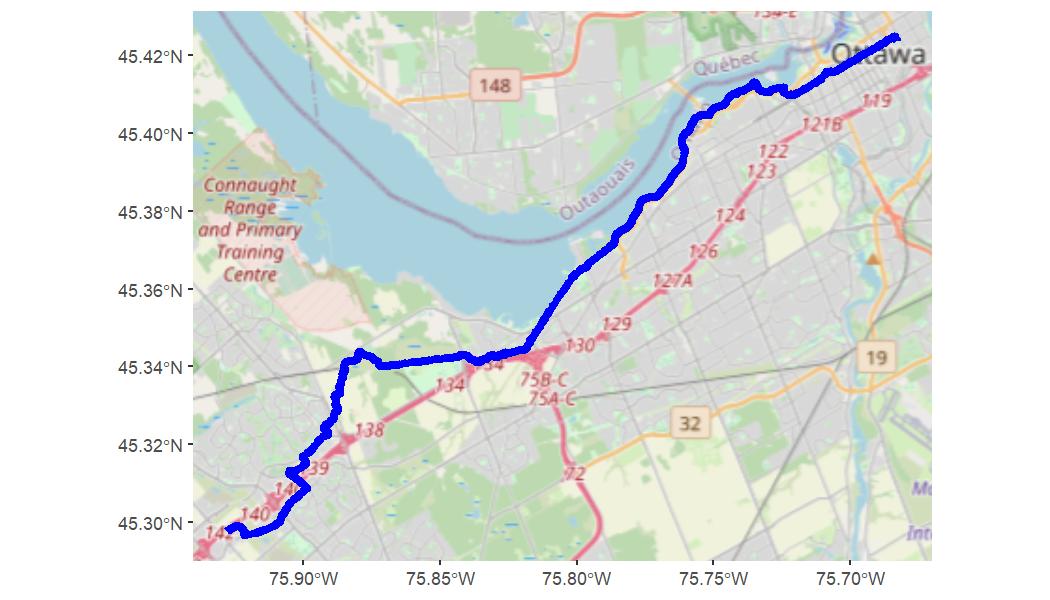

map_trip(t, method = "ggplot")What if we wanted to travel by bicycle instead? We can change our travel

method from the default, “auto”, using the costing parameter. Here we

set it to “bicycle” and re-run the command:

t <- route(from, to, costing = "bicycle")

print_trip(t)

#> From lat/lng: 45.4234, -75.6832

#> To lat/lng: 45.2975, -75.9279

#> Time: 108 minutes

#> Dist: 30.028 kmThis new trip is a bit longer at 30.028km, and would take quite a bit longer at 108 minutes. When we map it, we can see that Valhalla has given us a plausible cycling trip that takes a scenic route along the riverside path and avoids major highways:

map_trip(t, method = "ggplot")Many analyses require the shortest distance or time between a large

number of locations without needing to know the specific routes taken.

Sometimes this information is presented in origin-destination (OD)

matrices or OD tables, which simply show the shortest travel

distances/times between source locations and target locations. Valhalla

has an API called “sources_to_targets” to generate this information.

The valhallr package has two functions that call this API:

valhallr::sources_to_targets() calls it directly and provides

fine-grained access to configuration options, and valhallr::od_table()

provides a higher-level interface with several user-friendly features.

We’ll look at each function in turn.

In this example, we need to find the shortest distances and times between three source locations (the Canadian parliament buildings, the University of Ottawa, and the CN Tower) and two destination locations (the Canadian Tire Centre in Ottawa, and Zwicks Island Park in Belleville).

To create an OD table, we set up our sources in a tibble called froms,

our targets in a tibble called tos, and then pass them to

sources_to_targets() using all default options.

library(dplyr)

froms <- bind_rows(test_data("parliament"), test_data("uottawa"), test_data("cntower"))

tos <- bind_rows(test_data("cdntirecentre"), test_data("zwicksisland"))

st <- sources_to_targets(froms, tos)

st %>%

knitr::kable()| distance | time | to_index | from_index |

|---|---|---|---|

| 29.498 | 1232 | 0 | 0 |

| 273.969 | 10170 | 1 | 0 |

| 28.693 | 1194 | 0 | 1 |

| 273.164 | 10131 | 1 | 1 |

| 389.276 | 15963 | 0 | 2 |

| 190.912 | 7189 | 1 | 2 |

sources_to_targets() returns results as they come from Valhalla, which

has two disadvantages. First, it strips all human-readable names from

the inputs and only returns zero-indexed identifiers. And second, the

API call can fail for large requests with hundreds or thousands of

locations if Valhalla runs out of memory.

The valhallr::od_table() function addresses these two problems by

letting you specify human-readable names for each location, and by

letting you send origin rows to Valhalla in batches. The trade-off is

that od_table() doesn’t give as fine-grained access to the underlying

API, but it’s easier and faster for many purposes.

Here we can see the results of calling od_table() with the same inputs

as before, this time specifying the names of the human-readable id

columns in each input tibble:

od <- od_table (froms = froms,

from_id_col = "name",

tos,

to_id_col = "name")

od %>%

knitr::kable()| name_from | name_to | distance | time |

|---|---|---|---|

| parliament | cdntirecentre | 29.498 | 1232 |

| parliament | zwicksisland | 273.969 | 10170 |

| uottawa | cdntirecentre | 28.693 | 1194 |

| uottawa | zwicksisland | 273.164 | 10131 |

| cntower | cdntirecentre | 389.276 | 15963 |

| cntower | zwicksisland | 190.912 | 7189 |

The results are much easier to read, and would be simpler to feed forward into a further analysis (e.g. by left-joining with the original inputs to get the lat/lon information for mapping).

Although this example didn’t use batching, note that this can be essential for larger analyses and seems especially important when using “pedestrian” costing. For some analyses I’ve been able to use a batch size of 100 for “auto” costing but have had to scale down to a batch size of 5 for “pedestrian” costing.

Finally, valhallr provides access to Valhalla’s isochrone API

through the function valhallr::isochrone(). An isochrone, also known

as a service area, is a polygon that shows the area reachable from a

starting point by traveling along a road network for a certain distance

or time. This function lets you provide a starting point’s latitude and

longitude, a distance or time metric, and a vector of distances/times,

and if it’s successful it returns an sf-class tibble of polygons.

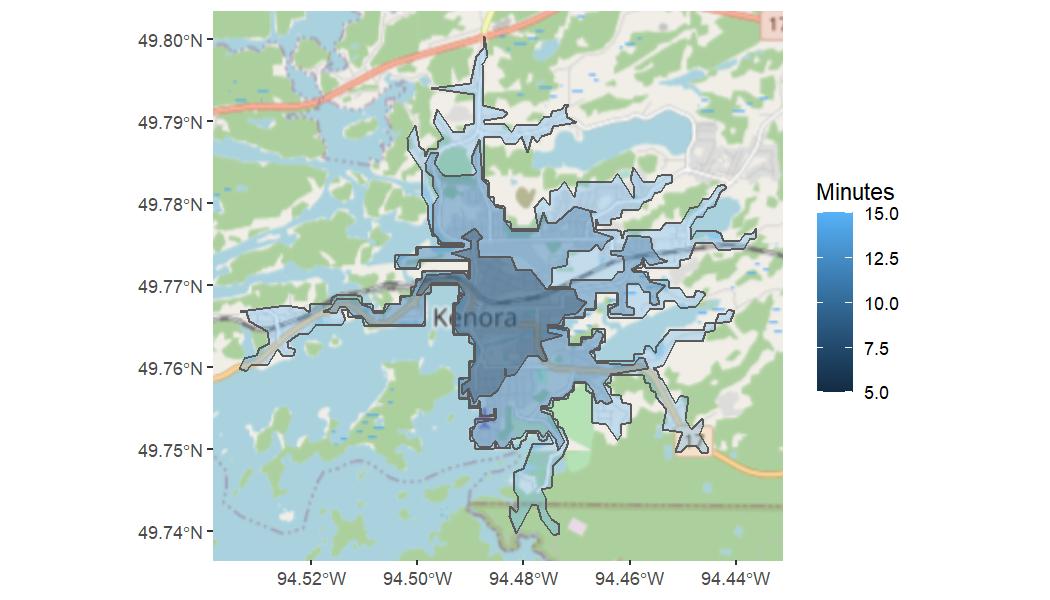

For example, how far can you get from downtown Kenora on a bicycle using the default values of 5, 10, and 15 minutes?

# set up our departure point: the University of Ottawa

from <- test_data("kenora")

# generate an isochrone for travel by bicycle

i <- valhallr::isochrone(from, costing = "bicycle")

# map the isochrone

map_isochrone(i, method = "ggplot")Pretty far, by the looks of it! You can see how the isochrones follow the road network, and so give a reasonably realistic estimate of how far you could travel.

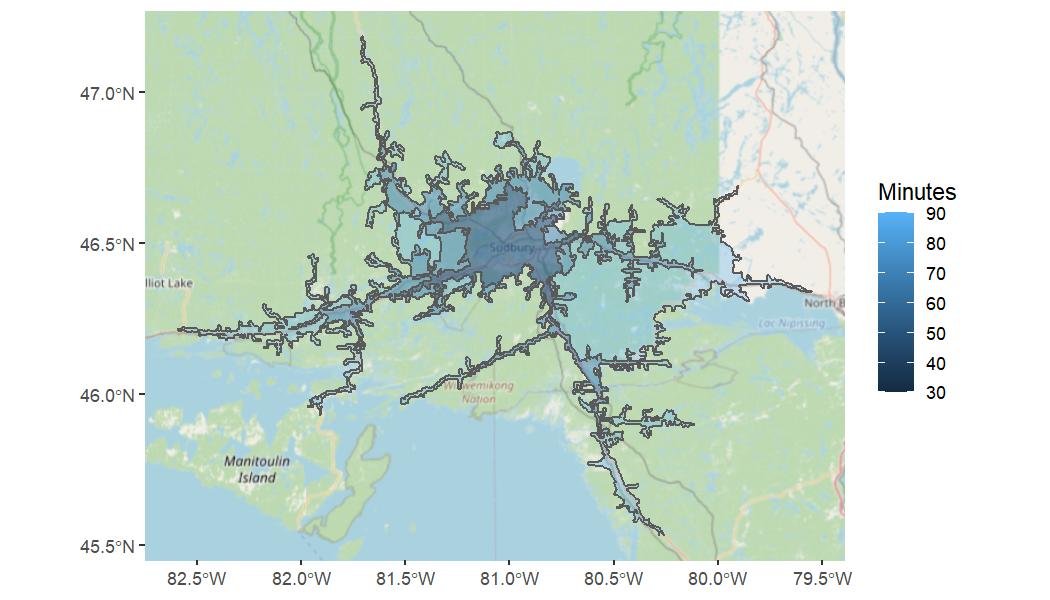

For another example, how far can you drive from Sudbury’s Big Nickel in 30, 60, and 90 minutes?

from <- test_data("bignickel")

i <- valhallr::isochrone(from, costing = "auto", contours = c(30,60,90), metric = "min")

map_isochrone(i, method = "ggplot")Again, quite far! You can see how the algorithm takes the road network and speed limits into account: once you get onto a major highway, the distances increase rapidly.